The world has come a long way in the fight against COVID-19, but new variants of the virus could threaten progress we’ve made over the past year.

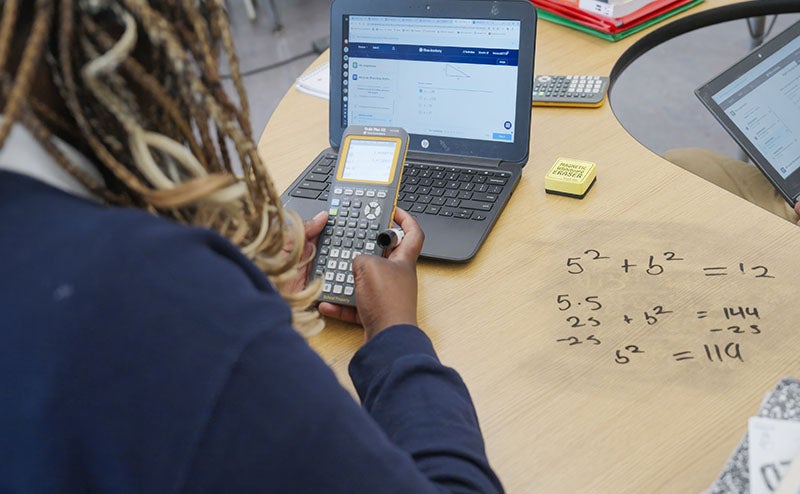

Education is one of the most challenging areas our foundation works on. There will never be a medicine that guarantees every child has access to a world-class education or a vaccine to prevent kids from dropping out. Each district has unique needs, and a good idea that works in one school might be difficult to scale across the entire system.

Melinda and I have evolved our thinking about education over the years, but one thing we remain committed to is innovation. I try to meet regularly with teachers and administrators in the field who have creative ideas about how to make school systems work for every child.

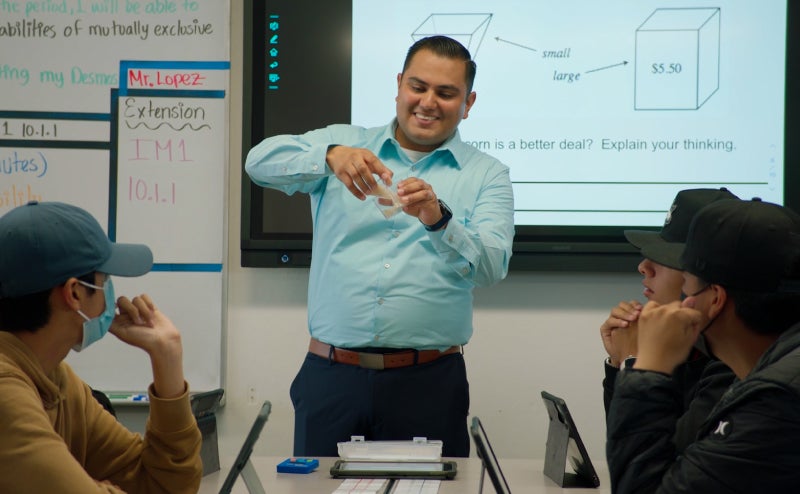

I recently had an insightful conversation with one of these big thinkers: Jorge Aguilar, the superintendent of the Sacramento City United School District. Although this is only his first year running his school district in Northern California, he’s already making a real difference in the lives of his students.

Jorge’s approach as an educator is shaped by his personal story. His parents were migrant farm workers from Mexico, and he split his childhood between a small town in California and his family’s hometown. When his senior year of high school came around, his parents didn’t know enough about the U.S. system to help him apply to college. He didn’t even know how community colleges differed from universities until a representative from the University of California visited his school.

Today, Jorge uses data to make sure kids like him don’t slip through the cracks. Twenty percent of the students in the Sacramento school district are still learning the English language, and approximately 70 percent are classified as low-income—two groups that are particularly at risk for falling behind academically. Jorge helped develop an early-warning system that looks at attendance, behavior, and academic records to detect kids who are more likely to drop out. His district also uses national college acceptance data to create recommendations for seniors about where they should apply.

“Data can keep you very human as long as you remind yourself that every numerator, every denominator is the face of a child,” he told me. “There’s just so many ways in which we can use data for this idea of making our work more human and taking a humanist approach.”

Jorge is also a big believer in what he calls an “opt-out philosophy” (it has nothing to do with opting out of tests). If a student excels at a particular subject, she gets automatically enrolled in college prep and other classes such as Advanced Placement. If she’s falling behind, the school signs her up for additional winter or summer classes. In both cases, parents must sign a form saying they don’t want their child to participate if they want to opt out.

He first implemented this approach in his previous job with the Fresno Unified school system. Jorge knew from the data that more Fresno students could benefit from extra instruction than were currently enrolled in summer school. Before the program, the entire district would see only four or five students sign up every year. After switching to an opt-out system, an impressive 18,000 students attended summer classes. He is now implementing a similar program in Sacramento.

I hope that eventually no child will need remedial instruction to succeed in the classroom. Until that day comes, I’m glad more students are getting the help they need. It’s too early to tell if Jorge’s approach is working in Sacramento, but I’m excited that he’s willing to try something new. I can’t wait to see the results.