I was especially struck by the central idea of his book, that we need to strengthen the reciprocal obligations we have to each other.

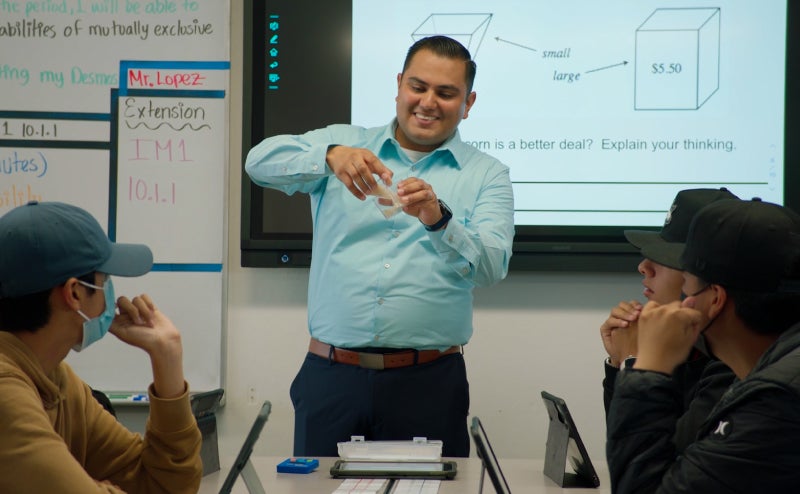

Every year, I look forward to meeting the Teacher of the Year for my home state of Washington. It’s always fascinating to hear educators at the top of their field talk about their classrooms.

This year’s conversation was different from the rest, though. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, I couldn’t sit down with Amy Campbell, this year’s recipient, in person. Like so many other meetings this year, this one had to happen over video chat. (The shots of Amy with her students in this video were filmed pre-pandemic.)

It's fitting that our meeting was unlike any other, because Amy is unique—and so are her students. Amy teaches special education at Helen Baller Elementary School in Camas, a small town just across the state border from Portland. All of her students have severe disabilities, so she has to come up with creative ways to draw them into their schoolwork.

I was impressed by how Amy customizes learning. She told me about one of her students, who is completely non-verbal, visually impaired, and can’t move his arms or legs. Rather than focus on what this student couldn’t do, Amy instead identified something he could do: nod and shake his head. She came up with a writing system based on yes-or-no questions, so that he could journal about what he did over the weekend with family just like all of his classmates.

Amy’s goal is to create an inclusive environment where her kids learn alongside their peers. Instead of the traditional model where special needs students are siloed into their own program, her students are integrated into the broader school. Each one learns and socializes in homeroom, eats in the cafeteria, and participates in recess and gym class.

The result is a school where students with special needs are treated as valuable and important members of the community. In addition to making sure her kids are integrated into the broader student body, Amy also works with the general population students to help them understand their differently-abled peers. They start learning and talking about disabilities in the classroom as early as kindergarten.

Of course, all of this has changed over the past few months. Like all teachers, she had to completely rethink the way her classroom works. In the spring, Amy, her teaching partner, and a group of paraprofessionals did one-on-one video sessions with each of her students most days. They also got the whole group together on Fridays. In between virtual classes, Amy worked with the parents to make sure they had all of the activities and materials they needed to keep their child’s education going.

Amy told me this close collaboration with parents has changed the way she’ll work with them moving forward. Over the last couple months, Amy has had to empower her students’ parents to use the techniques she employs in the classroom. “I will never teach the same,” she says. “Teachers shouldn't be the secret holder of the strategies that help students be successful.”

The pandemic has also helped Amy find new ways to use technology to break down barriers. Many of her students’ parents are finding it much easier to participate in school board meetings these days. Now that those meetings happen over Zoom, there is no need to arrange for childcare in order to attend.

Digital tools are doing the same for teacher collaboration. As Washington’s Teacher of the Year, Amy would normally take a half-year sabbatical from teaching and use this time to share her knowledge with other teachers around the state and country. Since the conferences and convenings where this knowledge-sharing happens are now digital, more people are able to join—including teachers from low-income schools who may not have had the resources to attend in person.

I admire Amy for finding some good in these circumstances. Still, on the whole, the pandemic has put teachers and parents in an impossible situation.

I asked her the question that’s top-of-mind for many of us: what will school look like in the fall? She told me many of her students are medically vulnerable, so returning to the classroom might not be an option for them even if their school opens. “School is so foundational to our communities and so important for vulnerable people,” she said. “My parents are exhausted. And yet, here they are facing the decision of ‘how do I protect my most valuable thing?’” (Amy’s school plans to start the school year remotely and gradually reintroduce in-person learning.)

Fortunately for those of us with kids in Washington, Amy is part of our state’s re-opening workgroup. She’s working with other educators and state officials to develop guidelines for the fall and help each district come up with a plan that makes sense for the community. She also helped create guidance for special education to make sure students with disabilities aren’t left behind.

In order to safely navigate this coming school year, we need teachers like Amy Campbell at the table making decisions. She’s a remarkable advocate for her students. Teaching special education takes an amazing person to figure out exactly what works for each child, and talking to her gave me an even greater appreciation for these educators. Amy’s students are lucky to have her in their corner.