By 2019, something remarkable had happened—what I consider to be one of the most important things humanity has ever achieved: In under three decades, child mortality was cut by more than half.

I often talk about the miracle of vaccines: With just a few doses, they protect children from deadly diseases forever.

When it comes to clean energy, we need breakthroughs that are just as miraculous.

Just like vaccines, clean-energy miracles don’t just happen by chance. We have to make them happen, through long-term investments in research and development. Unfortunately, right now neither the private sector nor the U.S. government is making anywhere near the scale of investment it takes to produce these breakthroughs.

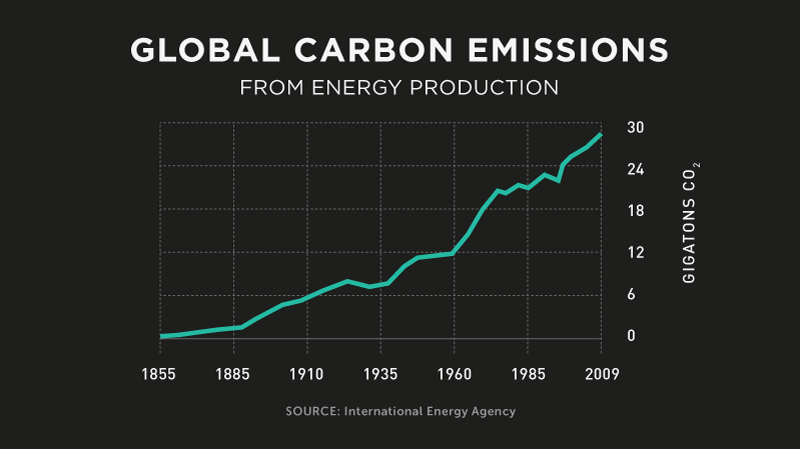

Why are clean-energy breakthroughs so important? As I mentioned here, the world is going to need a lot more energy in the coming decades—an increase of 50 percent or more between 2010 and 2040, according to U.S. government estimates. But today our biggest sources of energy are also big sources of carbon dioxide, which is causing climate change.

In other words, the world’s energy sources have to be clean, as well as reliable and affordable.

Today’s technologies are a good start, but not good enough. Some places don’t get enough regular sunlight or reliable wind to depend heavily on these sources. In any case, these and other clean-energy technologies are still too expensive to be rolled out widely in poor countries. They’re getting cheaper, but many developing countries aren’t waiting for these tools to become affordable. They’re building large numbers of coal plants and other fossil-fuel infrastructure now. That’s very unfortunate, but it’s understandable. We can’t expect them to wait decades for cleaner alternatives when their people need energy now.

That’s why we need a massive amount of innovation in research and development on clean energy: new ways to stabilize the intermittent flows from wind and solar; cheaper, more efficient solar panels; better equipment for transmitting and managing energy; next-generation nuclear plants that are even safer than today’s; and more.

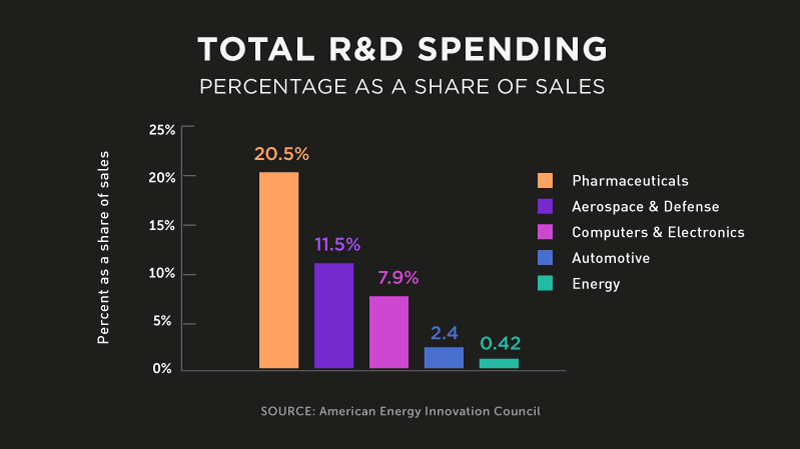

Unfortunately, the United States is severely underinvesting in clean-energy R&D. Let’s look at the two main sources of R&D investment. First there’s the private sector. Look at the chart below, which shows the percentage of sales that different industries put into R&D.

Why is energy so low? Because there’s a long lag time—often decades—before an investment in energy research delivers a commercial payoff (if it ever does). In addition, energy research results in a lot of public goods—economic competitiveness, national security, and environmental protection—that private markets don’t care much about.

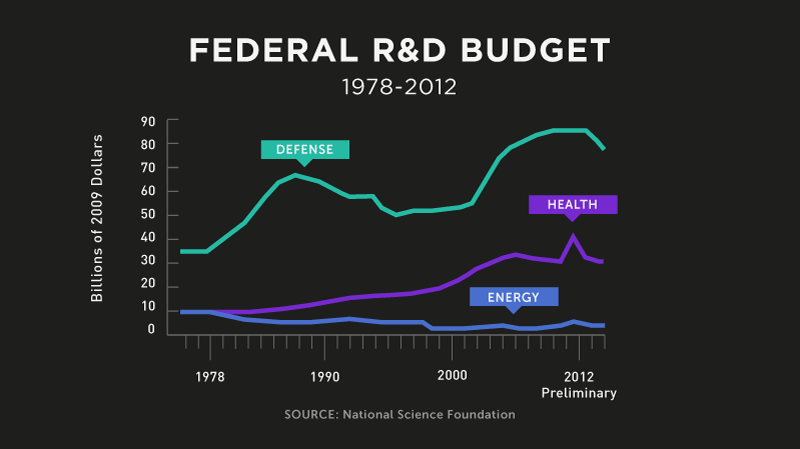

In theory, when private markets under-invest, government can step in. But in practice, the U.S. government isn’t investing nearly as much as it should either.

The chart below shows you how energy stacks up in terms of the overall federal spending on R&D. You can see that about 60 percent of the federal government’s R&D spending goes to defense. Around 25 percent goes to health. You can barely see energy at all—it’s just 2 percent.

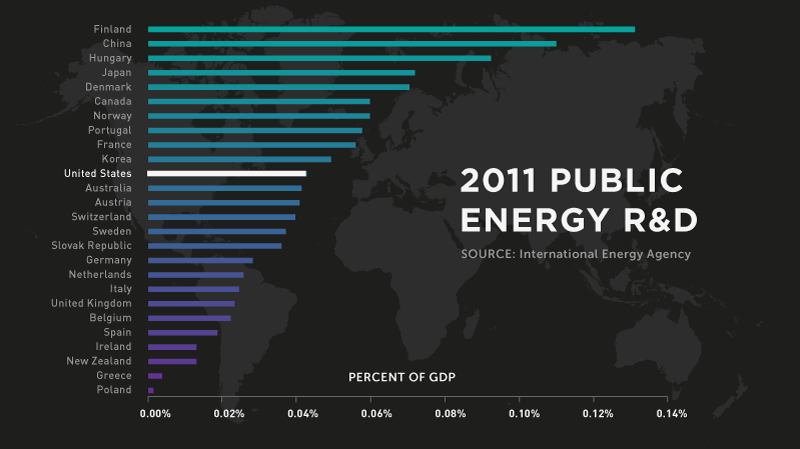

How do we rank among other countries? In terms of the percentage of GDP that goes to energy research, we rank 11th, behind China and Japan as well as Finland, Hungary, and Portugal.

Traditionally, the United States has been at the top in other areas of R&D. That’s why we’re a leader in IT, telecommunications, and other tech fields. By underinvesting in clean-energy research, we’re not only putting our global leadership at risk, we’re depriving researchers of funding that could shape the future of this crucial field.

What We Need to Do

I’m part of a business group called the American Energy Innovation Council, which is focusing intently on these issues. We have published two reports and a number of case studies, including one on how to unleash private sector R&D by doing things like expanding research grants and improving regulations. We’re also arguing that the federal government should adequately fund long-term research, roughly tripling energy R&D to $16 billion a year from the current $5 billion a year. Energy would then represent 6 percent of the total federal R&D budget.

That’s a lot of money, but given the scope of the challenge, I think it’s justified. It would unleash significant new investments in basic energy science, advanced nuclear fission, efficiency, renewables, improvements in the electricity grid, and more. This figure is also in line with recommendations from other groups, including the U.S. President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology and the International Energy Agency.

I’m optimistic that science and technology can point the way to big breakthroughs in clean energy and help us meet the world’s growing needs. In this area, like so many, there are no quick fixes, which makes it even more urgent to start work now.