Last year, the world saw the fewest number of polio cases—just 21, according to the latest figures.

If you live in the Pacific Northwest, you can’t find a better place to see a play than the Oregon Shakespeare Festival. I’ve been six or seven times, and I’m always blown away by the productions they put on. Some of the shows take place in this gorgeous outdoor theater that’s decorated like it’s from the Elizabethan era. There’s something special about seeing A Midsummer Night’s Dream or Othello under the stars.

The festival has made me even more of a fan of Shakespeare than I already was. I’m in awe of the timelessness and cleverness of his plays. It’s amazing how vivid, clever, and poignant his work remains centuries later.

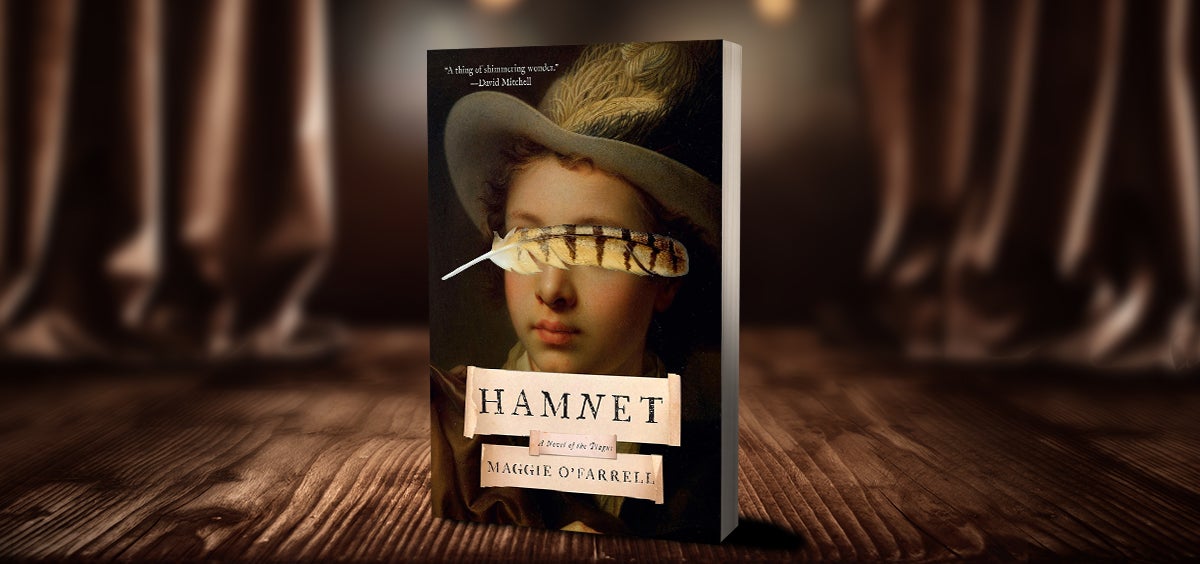

But who was Shakespeare really? We know shockingly little about the man behind the plays, although there have been a lot of films and books speculating about his personal life. (I’m particularly a fan of Shakespeare in Love.) Maggie O’Farrell’s novel Hamnet is the latest, and I thought it was a beautiful, well-written look at how grief tears a family apart.

O’Farrell centers her book on two things that we know are true: Shakespeare’s son Hamnet died at 11 years old, and Shakespeare wrote a tragedy called Hamlet just a couple years after his passing. (Many scholars believe that the names Hamnet and Hamlet were interchangeable in his era.) She explores the days leading up to Hamnet’s death and hypothesizes about how that event may have influenced the writing of one of the greatest plays of all time.

The most interesting choice she makes is to focus not on Shakespeare himself but on his family instead. The words “William” and “Shakespeare” are never used, and if you didn’t know what the book was about, I don’t know if you would recognize who “the husband” is until the end. You develop sympathy for him, but it’s really his wife, Agnes Hathaway, and their three children who are at the center of the story.

Agnes (whom most people probably know as Anne) is a fascinating character. She’s been painted by history as a calculating woman who trapped the much younger Shakespeare into marriage by getting pregnant, but O’Farrell has a different take on her. This Agnes is a mysterious and almost supernatural figure who has a deep connection with nature. She’s a talented healer who can see the future—she knows her first child will be a girl and that only two of her children will live to watch her die.

Most of Stratford-upon-Avon is afraid of her, but Shakespeare is drawn to the things that make her different and falls in love with her. When telling his sister about Agnes, he says, “She is like no one you have ever met... She can look at a person and see right into their very soul. There is not a drop of harshness in her. She will take a person for who they are, not what they are not or ought to be.”

When two of their children fall ill—first their younger daughter Judith, and then her twin Hamnet—Agnes is forced to care for them on her own. Shakespeare is in London working in the theater, and he only finds out that they’re sick once it’s too late.

No one knows what killed the real Hamnet. O’Farrell proposes that it was the bubonic plague, which is plausible for that era. It’s interesting to read about the plague right now, because it was such a different kind of pandemic than the current one. You wouldn’t see big outbreaks across entire communities. It would seem to show up randomly in a household, which is what happens to Agnes’s family.

You know from the beginning that Hamnet’s story is going to end in tragedy. It’s a testament to how talented of a writer O’Farrell is that you can’t but believe it might turn out differently and that Agnes might save him. It reminded me a bit of the George Saunders novel Lincoln in the Bardo. Both books imagine how historical figures would’ve responded to the loss of a child, although Bardo is a lot more fantastical. Sadly, this wasn’t an uncommon situation. Only two-thirds of children lived to see their fifth birthdays in Lincoln’s time, and the odds were much worse in Shakespeare’s day. O’Farrell and Saunders capture how devastating and shocking it is to lose a child, even in an era when it was somewhat expected.

Hamnet is ultimately a story about how the death of a son haunts his parents, while Hamlet is a tale about how the death of a parent haunts his son. O’Farrell cleverly ties the two together and offers a moving explanation for how Shakespeare channeled his grief and guilt into writing. She makes me want to go back and re-read the play.

If you’re familiar with Shakespeare’s writing, I think you’ll enjoy Hamnet. It’s surprisingly easy to read, even though the subject matter is heavy. I would describe it as emotional rather than depressing. At the end of the book, Agnes says she wishes she could “pierce the boundary between audience and players, between real life and play.” O’Farrell has done a remarkable job crossing that line and imagining how real life may have influenced one of history’s greatest plays.