The Power raises timely questions about gender dynamics.

Through my work at the foundation, I’ve been fortunate to meet some amazing people who have had a huge impact on the world. But, one person I’ll always wish I could have met is Norman Borlaug, a remarkable scientist and humanitarian whose work in agriculture has influenced my thinking and the foundation’s work with small farmers in the world’s poorest countries.

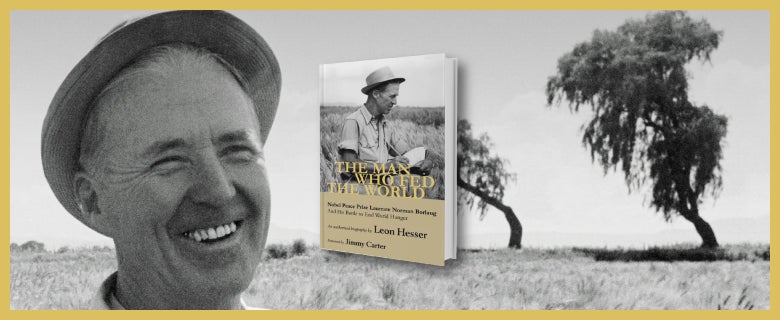

Fortunately, there is a great biography of Borlaug, The Man Who Fed the World, which I highly recommend. Although a lot of people have never heard of Borlaug, he probably saved more lives than anyone else in history. From the mid-1940s through the mid-1960s, Borlaug and a team of scientists successfully developed and introduced high-yielding, disease-resistant wheat seeds and new growing methods in Mexico, dramatically increasing the country’s agricultural production.

Just as Mexico was reaping the agricultural, social, and economic rewards of Borlaug’s efforts, tens of millions of people were on the verge of starvation in South Asia. One scientist, Paul R. Ehrlich, provocatively predicted in a controversial 1968 book, The Population Bomb, that hundreds of millions of people would die of starvation over the next few decades – no matter what anyone did.

Undeterred, Borlaug led the effort to ship thousands of tons of the wheat seeds developed in Mexico to farmers in India and Pakistan. In just a few years, wheat yields in both countries nearly doubled. India and Pakistan became self-sufficient in wheat production. And Borlaug, who became known as the father of the Green Revolution, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

It’s interesting to me how much criticism there has been of Borlaug over the years. It’s almost like people forget, or perhaps never really understood, what he did for humanity. It’s estimated that his new seed varieties saved a billion people from starvation.

But the significance of his work goes even further. When people get enough food to eat, their health improves and they are less susceptible to disease. In children, especially, improving their nutrition dramatically improves their brain and physical development. Much of the dramatic increase in productivity coming out of Asia over the last few decades is due to Borlaug’s Green Revolution.

One of the criticisms of Borlaug’s methods is the overuse of fertilizer. Even as great as his seeds were, they don’t grow magically. It’s true that there is a negative effect from the overuse of nitrogen, one of the key ingredients in fertilizer. It can flow into rivers and create algae blooms that kill fish. Today, as we look at increasing agricultural productivity, we do need to be smarter about how fertilizer is used in order to avoid these problems. For example, it can be applied in smaller doses near the root and irrigating can be done in a way that minimizes the flow of nitrogen into rivers.

The other main criticism was that the Green Revolution mainly benefited large farmers. In the first decade, it was those farmers who could afford fertilizer and understood seeds that did better. But in the second decade, there was an equally beneficial effect for small farmers. We do a lot of work through the foundation to help small farmers in poor countries, so we’re always watching out for inequities that hurt them.

Over time, the Green Revolution expanded to include other key crops such as rice and maize (corn). But for a variety of reasons, the agricultural innovation needed to create a breadbasket for Africa never got off the ground.

Seven or eight years ago, I came across a book, The Doubly Green Revolution, that really opened my eyes to the need for a Second Green Revolution to feed the hundreds of millions of people in Africa who are on the edge of starvation. The author, Sir Gordon Conway, a British agricultural ecologist, talks about the need for scientists and farmers in poor countries to work together to develop better plants and more sustainable agricultural practices. Conway also talked about the importance of creating better economic opportunities for poor farmers, who often are women.

Another book that influenced my thinking is The State of Humanity, a collection of essays edited by Julian Simon, an environmental economist. Simon believes in not underestimating the importance of technological innovation and human ingenuity in solving big problems that might seem insurmountable. This is a constant theme that I’ve always been interested in. When do people overestimate the power of innovation? When do they underestimate it? What do we need to do to foster it?

But most importantly, I have learned what’s possible in agriculture from studying Borlaug and what’s happened in the decades since his breakthroughs. We know that we need to encourage a sustainable model of agriculture. And we understand that small farmers in Africa and South Asia must be involved in developing and testing the agricultural advances needed to feed the hundreds of millions of people who are still going to bed hungry most nights.

Norman Borlaug was one-of-a-kind—equally skilled in the laboratory, mentoring young scientists, and cajoling reluctant bureaucrats and government officials. The second Green Revolution may not produce another Norman Borlaug, but his achievements and influence will continue to guide our work at the foundation and in agricultural development around the world.