I planted drought-tolerant seeds, fed and weighed chickens, and used a mobile phone to monitor weather forecasts and local crop prices.

My last holiday books list included a novel called An American Marriage which really stuck with me over the previous year. I was deeply touched by its story of a husband torn away from his wife by a false accusation that lands him in prison. The book did a beautiful job of showing how incarceration can devastate a family, even after release from prison.

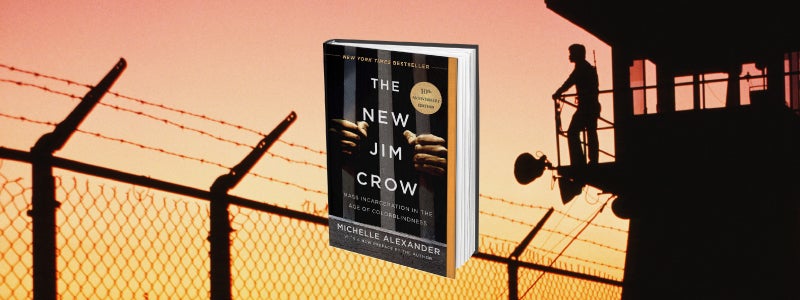

As moving as the book was, the story was fiction. But the idea of a family torn apart by mass incarceration is not. If you’re interested in learning more about the real lives caught up in our country's justice system, I highly recommend The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander. It offers an eye-opening look into how the criminal justice system unfairly targets communities of color—and especially Black communities.

The book was released more than 10 years ago, but this is a topic that has taken on extra relevance this year. The horrifying killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor set off a summer of protests that put Black Lives Matter front and center. Like many white people, I’ve committed to reading more about and deepening my understanding of systemic racism. Alexander’s book is about much more than the police—whom she describes as the “point of entry” into the justice system—but it provides useful context to understand how we got to where we are.

Alexander explains how mass incarceration is a cycle. Once you’ve been in prison, you can’t often get a job after you get out because having a felony on your record makes it hard to get hired. In some cases, the only way to make money and support your family is through illicit means—which can land you back in prison. The result of this cycle is a permanent underclass that is disproportionately Black and low-income. (Alexander also talks about this in Ava DuVernay’s excellent documentary 13th.)

The book is good at explaining the history and the numbers behind mass incarceration. I was familiar with some of the data, but Alexander really helps put the numbers—especially around sentencing and the War on Drugs—in context. The New Jim Crow was published a decade ago, so some of the figures are outdated. The incarceration rates have only gone down a tiny bit in the last ten years, though, and the general picture she paints is still highly relevant.

Alexander argues that the criminal justice system has been the primary driver of racial inequity in America since the end of the Jim Crow era (hence the book’s title). The U.S. is unique in putting so many people in jail for such long periods. We lock people up at five to ten times the rate of other industrialized countries according to the Sentencing Project, and prison spending has risen three times faster than education spending over the last three decades.

I was particularly shocked to read the stories Alexander uses to illustrate the extreme sentences that many judges are forced to hand down. Because of how sentencing laws are often structured, judges sometimes don’t have “judicial discretion”—the ability to make decisions based on their personal evaluation of the defendant. Their hands are tied, especially in drug cases. Alexander tells the story of one federal judge who broke down in tears when he was forced to sentence a man to “ten years in prison without parole for what appeared to be a minor mistake in judgment in having given a ride to a drug dealer for a meeting with an undercover agent.”

It’s clear that we need a more just approach to sentencing and more investment in Black communities and other communities of color. The good news is that support for change is growing. Although there has only been modest progress on this front since The New Jim Crow was published in 2010, a new bipartisan coalition has emerged in support of prison reform in that time. (I met with a bipartisan group to learn about the subject during a trip to Georgia in 2017.) And I am hopeful that this year’s protests for Black lives—which are now considered the largest movement in U.S. history—will go a long way toward building more public support for updating our justice system.

I hope Alexander plans on writing a follow-up to The New Jim Crow someday. The latest edition includes a new preface that touches on the Black Lives Matter movement, but it was published before the events of this summer. She’s so good at explaining the historical context behind the injustices that Black people experience every day, and I am eager to hear her thoughts on how this year might have moved us closer to a more equal society.