I came home with a deeper understanding of India’s vibrant innovation ecosystem and how it’s generating major advances in health, urban poverty, digital services, and much more.

It’s a wonderful time of the year: commencement season. While I never finished college myself, I’ve been fortunate enough to watch two of my kids graduate already. I know the hard work and late, caffeine-fueled nights that go into making a moment like this a reality. So, class of 2023, congratulations.

Later this week, I’ll be heading to Northern Arizona University to commend the graduates of the College of Engineering, Informatics, and Applied Sciences and the College of the Environment, Forestry, and Natural Sciences—and share a few other words of advice—in person. I don’t give commencement speeches often, but I’m excited to be giving one at NAU because something remarkable and all too rare is happening in Flagstaff: The school is redefining the value of a college degree.

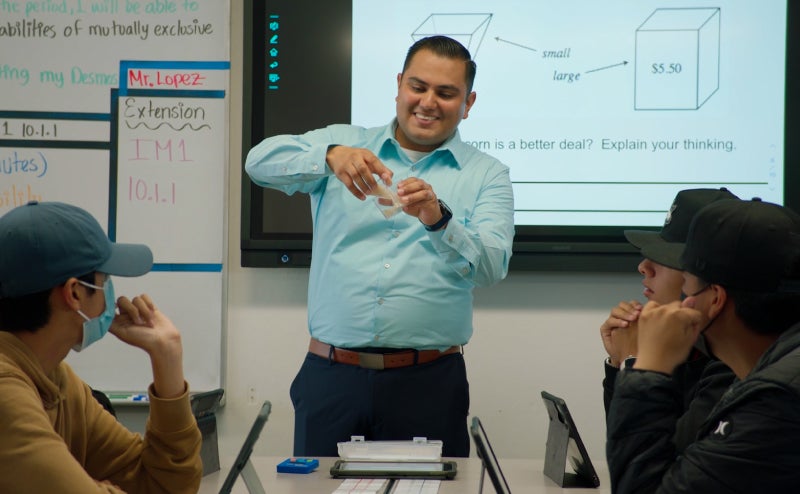

In America, the value of a degree from any given school is traditionally thought about in terms of how prestigious and exclusive the school is. Of course, things like alumni network, course offerings, campus life, and professor quality are factored in, too. But in general, conversations about higher education tend to focus more on the students’ input than the school’s output: more on the scores and extracurriculars required for admission than the skills and credentials acquired by graduation—and whether those skills and credentials translate into well-paying jobs for large numbers of students. Ironically, the more students a school accepts and the easier it is to attend and graduate from, the lower that school has traditionally been ranked.

That’s an inverted incentive if ever one existed. America’s world-class schools are one of our greatest strengths, yet we rank 14th among G20 countries in our percentage of 25-to-34-year-olds with a higher education. That’s bad for the country, and for students themselves: Studies have shown that college graduates live longer, earn more on the job, and are more civically engaged, among a host of other benefits. But any old degree doesn’t cut it. A piece of paper doesn’t qualify someone for work or improve their life; the education it’s meant to represent does. So we don’t just need more degrees—we need more valuable ones.

Back in 2019, the Gates Foundation helped form a commission to tackle this issue. The goal was to improve returns on higher education for students and families, and to help policymakers and college leaders understand which institutions were providing positive returns, which ones were falling short, and why. To start, the commission landed on a new way to define the value of a college education—by the payoff it provides to students and society—and a better way to measure it: by putting aside exclusivity, and putting accessibility, affordability, and economic mobility at the center instead.

By that definition and those metrics, NAU is an emerging leader.

Initially named the Northern Arizona Normal School when it was founded in 1899, NAU has always been anything but normal. Its first graduating class, just two years later, was made up of four women. During the Great Depression, the school created jobs for students—at an affiliated farm, in kitchens around campus, as newspaper deliverers—so they could afford tuition and stay enrolled. Even the first Hopi student to get a college degree, Ida Mae Hoonmona Fredericks, got hers here.

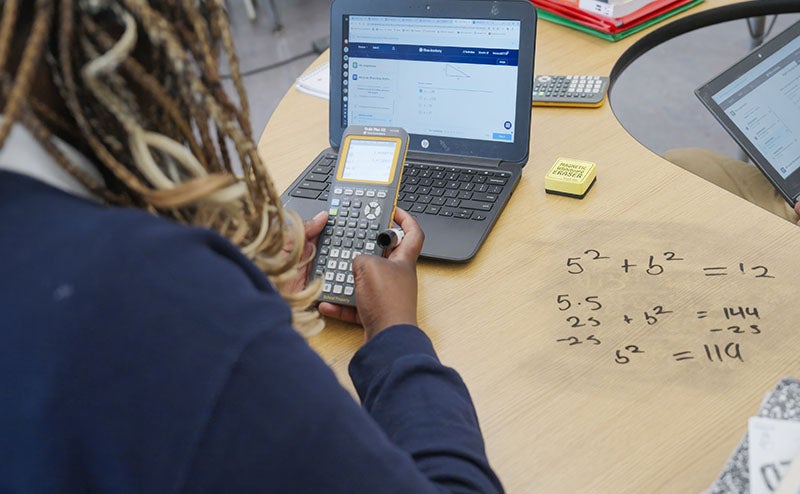

Today, almost half of NAU’s nearly 30,000 students are people of color, many of them Hispanic or Native American. Most come from in-state, half are first-generation college students, and many come from low-income families. The school has long been an engine of mobility for such students—but in 2021, NAU President José Luis Cruz Rivera helped revitalize the school’s charter to make delivering equitable postsecondary value to students the top priority and goal. Then NAU made a number of changes to accelerate that progress.

For example, as a longtime partner to the state’s community colleges, NAU recently launched a universal admissions program, which redirects applicants who would have been denied entry to instead apply to community college. From there, students are guaranteed subsequent admission to NAU as a transfer—no additional application needed. NAU has also secured millions in scholarships and advising services for community college students who intend to transfer to NAU and helped identify academic pathways that prepare those students for Arizona’s high-skills, high-demand, and high-wage jobs.

And beginning this fall, NAU’s Access2Excellence program is making tuition free for students with family incomes below the state’s median of $65,000, as well as for all Native American students from one of Arizona’s 22 federally recognized tribes. This is just one way the school goes above and beyond to serve its Native American students and respect the university’s connection to tribal land. For example, the Forestry School incorporates knowledge from local tribes into how it teaches land management. The university is also expanding who qualifies for guaranteed admission: any Arizona high school graduate with a 3.0 GPA or higher—including the 50,000 students attending schools that don’t offer all of NAU’s required courses, many of them from low-income communities, who had been ineligible for admission due to something out of their control.

That’s just the start of NAU’s impressive reforms. I can’t wait to be in Flagstaff and take it all in up close. Although I will be there to share whatever wisdom I can with the graduates, I imagine that with an NAU degree in hand—and the value of an NAU education behind them—they’ll have a lot to teach me, too.