Without any women’s teams to join, Jeanne d’Arc trained on her own.

Today I’m in the town of Kemmerer, Wyoming, to celebrate the latest step in a project that’s been more than 15 years in the making: designing and building a next-generation nuclear power plant. I’m thrilled to be here after all this time—because I’m convinced that the facility will be a win for the local economy, America’s energy independence, and the fight against climate change.

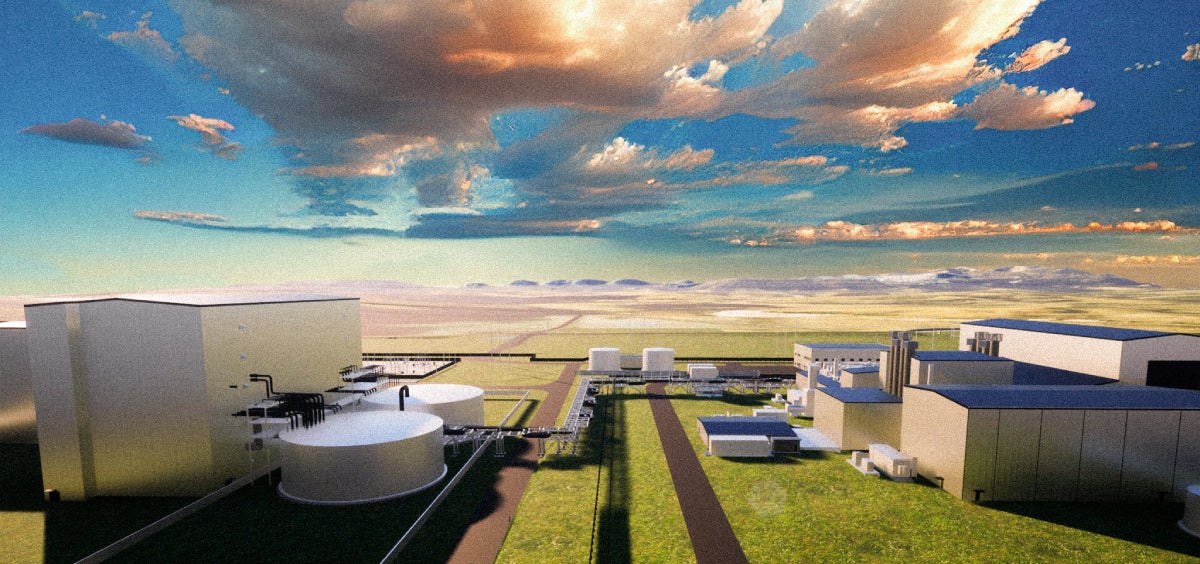

It’s called the Natrium plant, and it was designed by TerraPower, a company I started in 2008. When it opens (potentially in 2030), it will be the most advanced nuclear facility in the world, and it will be much safer and produce far less waste than conventional reactors.

All of this matters because the world needs to make a big bet on nuclear. As I wrote in my book How to Avoid a Climate Disaster, we need nuclear power if we’re going to meet the world’s growing need for energy while also eliminating carbon emissions. None of the other clean sources are as reliable, and none of the other reliable sources are as clean.

But nuclear has its problems: The plants are expensive to build, and human error can cause accidents. Plus, as we move away from fossil fuels, there’s a risk that we’ll leave behind the communities and workers who have been providing reliable energy for decades.

The Natrium facility is designed to solve these problems, and more.

I’ll start with improved safety. Keep in mind that America’s current fleet of nuclear plants has been operating safely for decades—in fact, in terms of lives lost, nuclear power is by far the safest way to produce energy. And this new facility in Kemmerer will be even better.

Like other power plant designs, it uses heat to turn water into steam, which moves a turbine, which generates electricity. And like other nuclear facilities, it generates the heat by splitting uranium atoms in a chain reaction. But that’s pretty much where the similarities stop.

A typical reactor keeps the atom-splitting nuclear reaction under control by circulating water around a uranium core. But using water as a coolant presents two challenges. First, water isn’t very good at absorbing heat—it turns to steam and stops absorbing heat at just 100 degrees C. Second, as water gets hot, its pressure goes up, which puts strain on your pipes and other equipment. If there’s an emergency—say, an earthquake cuts off all the electricity to the plant and you can’t keep pumping water—the core continues to make heat, raising the pressure and potentially causing an explosion.

But what if you could cool your reactor with something other than water? It turns out that, by comparison, liquid metals can absorb a monster amount of heat while maintaining a consistent pressure. The Natrium plant uses liquid sodium, whose boiling point is more than 8 times higher than water’s, so it can absorb all the extra heat generated in the nuclear core. Unlike water, the sodium doesn’t need to be pumped, because as it gets hot, it rises, and as it rises, it cools off. Even if the plant loses power, the sodium just keeps absorbing heat without getting to a dangerous temperature that would cause a meltdown.

Safety isn’t the only reason I’m excited about the Natrium design. It also includes an energy storage system that will allow it to control how much electricity it produces at any given time. That’s unique among nuclear reactors, and it’s essential for integrating with power grids that use variable sources like solar and wind.

Another thing that sets TerraPower apart is its digital design process. Using supercomputers, they’ve digitally tested the Natrium design countless times, simulating every imaginable disaster, and it keeps holding up. TerraPower’s sophisticated work has drawn interest from around the globe, including an agreement to collaborate on nuclear power technology in Japan and investments from the South Korean conglomerate SK and the multinational steel company ArcelorMittal.

I can’t overstate how welcoming the people of Kemmerer are being. While I’m here, I’ll get to visit the future site of the plant, and I’ll also have a chance to talk with the mayor, other local leaders, and members of the community so I can thank them for their efforts. And this project wouldn’t be happening without strong support from Gov. Mark Gordon and Senators John Barrasso and Cynthia Lummis.

Kemmerer has a particular interest in the Natrium facility’s success: The coal plant that has been operating here for more than 50 years is scheduled to shut down. If it weren’t for the Natrium plant, the 110 or so workers there would lose their jobs.

But the plan is for all of them to get jobs in the Natrium facility if they want one. The new plant will employ between 200 and 250 people, and those with experience in the coal plant will be able to do many of the jobs—such as operating a turbine and maintaining connections to the power grid—without much retraining.

Another benefit: Building the facility will take several years and at its peak will bring 1,600 construction jobs to town. And all those construction workers will need food, housing, and entertainment. It’ll be a huge boost to a community that could use one right now.

Finally, I’m excited about this project because of what it means for the future. It’s the kind of effort that will help America maintain its energy independence. And it will help our country remain a leader in energy innovation worldwide. The people of Kemmerer are at the forefront of the equitable transition to a clean, safe energy future, and it’s great to be partnering with them.